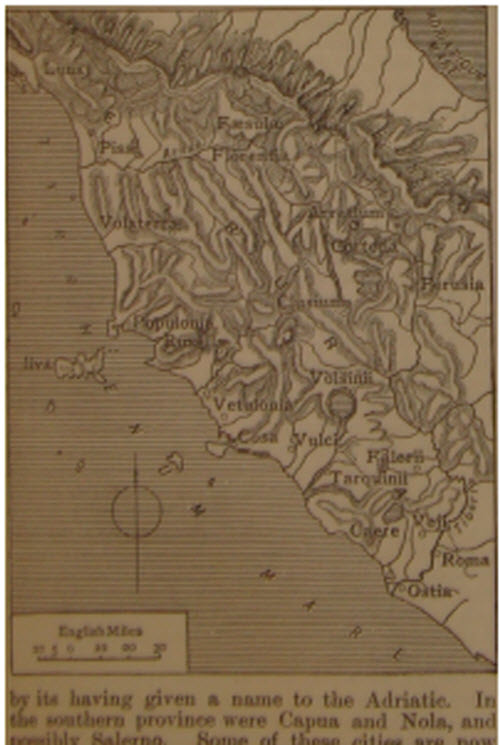

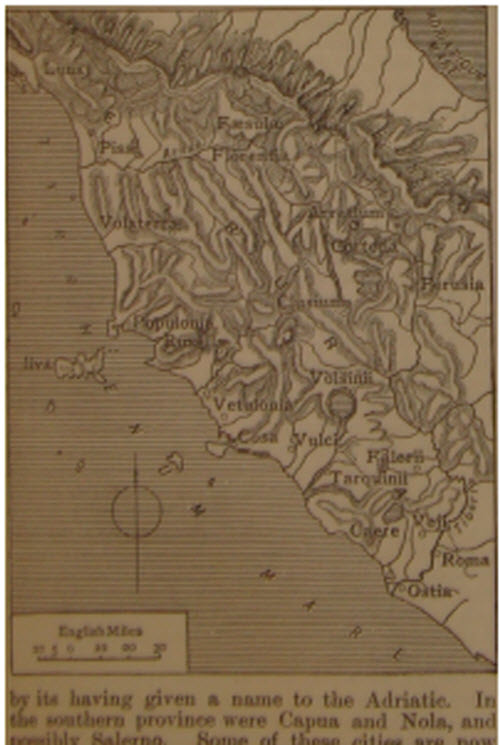

Map of Etruria

Etruria was the country of the Etruscans, a very ancient people of Italy. Etruria Propria lay west of the Tiber and the Apennines, and included the valley of the Arno. In the 6th and 5th centuries B.C. the Etruscans held also the valley of the Po, called Etruria Cir-cumpadana, and a region south of the Tiber, called Etruria Campaniana. Etruria Propria was a confederation of twelve cities or states, the duodecim populi Etruriae. No list of these cities has come down to us, but Veii, Tarquinii, Caere, Clusium, Cortona, Perusia, Vulci, Volsinii, Vetulonia, Volaterrae, and Arretium may probably be included, while the twelfth may have been either Rusellae, Falerii, or Populonia.

Map of Etruria

To the northern confederation twelve cities are also assigned; among them we may reckon Mantua, Chiavenna, Felsina (Bologna), Ravenna, and Hatria, whose importance is shown by having given its name to the Adriatic. In the southern province were Capua and Nola, and possibly Salerno. Some of these cities are now deserted sites, marked only by vast cemeteries and the remains of cyclopean walls, while others still retain more or less of their old importance.

Veii, for four centuries the formidable foe and rival of Rome, from which it is only 11 miles distant, is now utterly desolate. It was taken and destroyed by Camillas in 396 B.C. The necropolis, extending over 16 sq. m., attests the splendour of the ancient city and the vast population which must have dwelt within its walls, 7 miles in circuit. Six miles from the sea, midway between Rome and Civita Vecchia, is the village of Cervetri, which preserves the name and marks the site of Caere, which, under its older name of Agylla, is said to have been a "Pelasgian" city before the arrival of the Etruscans.

On this site inscriptions have been found, written in a language and an alphabet called "Pelasgic," and believed to be pre-Etruscan. The paintings in some of the tombs are in a style no less archaic. Of later date is the tomb of the Tarquins, who are said to have fled to Caere when expelled from Rome. Cortona, perched upon a rock, and surrounded by fragments of massive walls, possibly of pre-Etruscan date, occupies the most venerable site in Italy. In the time of Herodotus, Cortona, like Caere, retained its ‘Pelasgic’ character. Dionysius says it was a great and flourishing city of the Umbrians before it was taken by the Etruscans, who made it their northern capital.

The bronze-workers of Cortona were renowned, and the local museum contains noteworthy examples of their skill. The southern capital was Tarquinii, a city purely Etruscan. Corneto, a town 60 miles from Rome, and not far from the sea, occupies a portion of the site. The necropolis of Tarquinii, which extends over many miles, contains several sepulchral chamber painted in the archaic style of the genuine art of the Etruscans, and giving a curious insight into their religious beliefs.

We have scenes from the under-world, representing souls riding on horseback or seated in cars, led away in the charge of good or evil spirits. Elsewhere the daily life of the people is depicted; we see horsemen returning from the chase, chariots, boar-hunts, wrestlers, pugilists, banqueting scenes, dancing girls, and musicians. Fig. 1 represents a dancing girl and musicians from the walls of a tomb called the Grotta del Trinclinio, and fig. 2 a death-scene from a tomb called the Camera del Morte. The tombs of Clusium (now Chiusi) exhibit the same archaic character as those of Tarquinii. A vast chambered tumulus called the Poggio Gajella is probably that described by Varro as the tomb of Lars Porsena. Vulci, though barely mentioned by historians, must have been a very wealthy and populous city. The necropolis has yielded a richer treasure of artistic objects than any other Etruscan site.

The Cucumella, a huge chambered tumulus like that at Clusium, bears a curious resemblance to the great tomb of Alyattes, king of Lydia, the father of Croesus, near Sardis. Volsinii gave its name to Lake Bolsena, on whose shores it stood. It was one of the most powerful Etruscan cities, and one of the last to yield to Rome. From Volsinii we have few monuments or inscriptions, the necropolis not having yet been found. On the other hand, Perusia (now Perugia) has yielded 1200 inscriptions, among them the famous cippus, a stone containing the only Etruscan inscription of considerable length. It has not been deciphered, but appears to be the record of the assignment of a sepulchre to the Velthina family.

Velathri (now Volterra), called Volaterrae by the Romans, stands, like Cortona, upon an almost im-pregnable rock, surrounded by Etruscan walls, five miles in circuit. It held out against the Romans after all the rest of Etruria had been subdued. The people burned their dead instead of burying them, and the local museum contains 400 ash-chests, like miniature sarcophagi, the sides carved with mythological subjects, or with representations of bull fights, boar hunts, horse races, and gladiatorial combats.

Cyclopean walls mark the sites of Rusellae, Cosa, Saturnia, and of Pupluna (Popu-lonia), a seaport, interesting chiefly for its coins. The walls of Faesulae (Fiesole), near Florence, are well known to travellers. Orvieto ( Urbs Vetus) must have been an important Etruscan site, but its ancient name is unknown. Vetulonia was probably near Magliano, a squalid village in the Maremma. Neither Luna nor Pisae has yielded any remains of interest. Other Etruscan sites, among them Viterbo (Surrina), Bologna (Felsina), Toscanella (Tuscania), Siena (Senae), Arezzo (Arretium), Sovana (Suana), and Ferento (Ferentium), are described by Dennis, Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria (2d ed. 1878), to which the reader may be referred for fuller information.