Sarcophagous Depicting the Occupant in Life

The history of the Etruscans, like that of Carthage, has to be reconstructed from accounts transmitted by hereditary foes. The Roman legends represent Etruria as a powerful and wealthy state before Rome was founded. According to a tradition preserved by Varro, the Etruscan era commenced in 1044 B.c., nearly three centuries before that of Rome.

Sarcophagous Depicting the Occupant in Life

When legend ceases and history begins, we find the Etruscans a great naval power, allied with Carthage against the Greeks, and dominant throughout northern and central Italy, Rome itself being included in the Etruscan dominion, and ruled by Etruscan kings. The legend of the migration of the Tarquin dynasty from Tarquinii may signify the extension of the domination of that powerful city over the regions southward of the Tiber. A cemetery, believed to be Etruscan, has been discovered on the Esquiline, and the Caelian Hill in Rome bears the name of the Etruscan chieftain Caeles Vibenna.

The paintings and inscriptions in a tomb at Vulci give an Etruscan version of the Tarquinian story. We see the hero ‘Macstrna’ (Mastarna), an Etruscan appellation Applied to Servius Tullius, cutting the bonds of his friend and companion Calle Vibinas (Caeles Vibenna), while Cneve Tarchunies Rumach (Cn. Tarquinius Romanus) in being killed by an Etruscan. The names of Tarquin, Mastarna, and Caeles Vibenna, thus curiously preserved, prove that Livy’s account of the Etruscan kings of Rome is not wholly legendary. But that it was not derived from contemporary sources is indicated by a recent discovery of considerable interest. We learn that in 509 B.C. Lars Porsena of Clusium, as Livy calls him, marched with a great army to the gates of Rome to replace Tarquin on the throne.

Now, in a newly opened tomb at Vulci, a sarcophagus was found, on which is depicted in relief a high official with insignia resembling those of a Roman consul. He is riding in procession on a biga, preceded by two lictors with their fasces, and followed by two servants. The inscription informs us that this deceased magistrate, Tute Larth, was purtsvana thuns, ‘five times Porsena.’ It is manifest that Porsena was not, as Livy supposed, a proper name, but, like Pharaoh in Egypt, the designation of an office; and that the Etruscan chief who took up Tarquin’s cause was the elected ‘ Porsena ’ or chief-magistrate of Clusium.

In like manner, since the word machs meant ‘ first’ in Etruscan, it seems probable that Macstma, the Etruscan appellation of Servius Tullius, was not a proper name, but a designation of the kingly office, equivalent, it would seem, to Princeps. We are also told that Tarquin, with his two sons, Titus and Aruns, took refuge in Caere. Not only are Tite and Arnth usual names in Etruscan epitaphs, but at Cervetri, the site of Caere, there is an immense chambered tomb containing mortuary records of forty-six members of the Tarcna family, which must have been resident at Caere for many generations.

As an Etruscan city, Rome plainly attained a greater height of prosperity than she regained for two centuries. This is indicated not only by the legends of the splendor of the Tarquinian kings, but by the evidence of such vast constructions as the Cloaca Maxima, the Capitoline temple, and the Servian wall. The state ceremonial of Rome appears also to have descended from the period of Etruscan rule. The insignia of consular authority, the toga praetexta with its purple border, the ivory curule chair, the twelve lictors with their fasces and axes, all of Etruscan origin, are not likely to have been copied from the usages of hereditary foes, but are more probably survivals from the period when Rome was one of the Etruscan cities.

An Etruscan origin may also be assigned to the circus, the gladiatorial combats, the horse-races, the triumphal processions, the pipe-players, the lituus, the colleges of augurs, as well as the arrangement of the house, the art of constructing aqueducts and sewers, the division of the as into twelve parts, the beginnings of military science, and some of the Roman weapons. More than all, the high position of the wife, so different from that which she occupied in Greece, was the same as that which she occupied in Etruria.

How feeble was the Roman republic in its infancy appears from the fact that for a century after the expulsion of her Etruscan lords Rome maintained with varying fortunes the struggle with the Etruscan town of Veii, distant 11 miles only from her gates. That Veii fully held her own is shown by the admission that in the year 476 B.c. she captured the Janiculum. At that time the Etruscans were still the greatest military power in Italy. At the height of their prosperity, in the 6th century B.C., they shared with the Phoenicians and the Greeks the maritime supremacy of the Mediterranean.

In 538 B.C., in conjunction with the Carthaginians, they sent a powerful fleet to expel the Greek colonists from Corsica. They attacked the Greek colony of Cumae in 525 B.C., and again in 474 B.C., when their naval power was shattered by Hiero I. of Syracuse, in a great battle fought off Cumae, the first event in Etruscan history as to which we possess contemporary records. The victory was celebrated by an ode of Pindar, then resident at the court of Hiero; while from the inscription on a bronze helmet, found at Olympia in 1817, and now in the British Museum, we learn that it was an Etruscan trophy from Cumae, dedicated by Hiero and the Syracusans to the Olympian Zeus. In 453 B.c. we find the Etruscans still in possession of Corsica, and in 414 they were able to send a contingent of three ships to aid the Athenians at the siege of Syracuse.

But from this time dates the rapid declension of their power. Towards the close of this century the Etruscan dominion in Campania was overthrown by the Samnites and the Greeks of Cumae, Capua being taken by the Samnites in 423. Then the Gauls swarmed over the Alps, and, after overwhelming the Etruscan cities in the valley of the Po, crossed the Apennines, having destroyed the wealthy city of Melpum in 396 B.C., the year in Which the long struggle between Rome and Veii was brought to an end by the capture of the latter by Camillus, after a ten years’ siege. The Gauls continued their devastating progress through Etruria, and in 390 plundered Rome, after having vainly laid siege to Clusium.

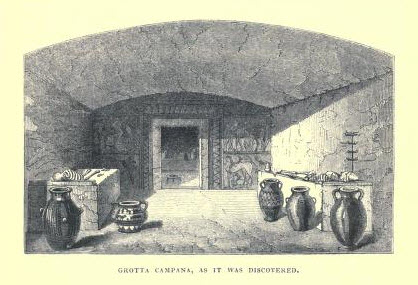

Burial Chambers Were Designed to Look Like the Houses of the Living

Etruria was fatally weakened by the loss of her two outlying provinces and the devastation of the central province by the Gauls. After a prolonged resistance, southern Etruria submitted to Rome in 351 B.C.. In 311 war was renewed; the Romans crossed the natural boundary formed by the Ciminian Forest, and, after repeated defeats of the Etruscans, a decisive contest took place in 283 at the Vadimonian Lake, when Tarquinii lost its independence; and three years later the Romans reached Volaterre, the northern stronghold of the Etruscans, when the struggle, which had endured for five centuries, came finally to an end.

In the Second Punic War, the chief Etruscan cities furnished supplies for the Roman fleet. It is plain that these cities retained wealth and power as semi independent allies under the Roman suzerainty. They seem to have been gradually Romanized, and were finally admitted to the Roman franchise in 89 B.C. The great Etruscan families secured leading positions in the Roman commonwealth.

Pompey the Great seems to have been of Etruscan lineage, tombs of the Pumpu family having been discovered at Corneto (Tarquinii), Clusium, Cortona, and Perugia. There was a Tarquinian gens at Rome in the time of Cicero, while Maecenas, who bears an Etruscan name, was from the Etruscan city of Arretium (Arezzo). Families of undoubted Etruscan lineage still linger on in Etruria. The necropolis at Volterra contains the tomb, with Etruscan epitaphs, of the Ceicna (Caecina) family, members of which distinguished themselves under the early emperors, and whose lineal representative, Nicolas Caecina, bishop and patrician, was buried in the cathedral of Volterra in 1765.